Community and Urban Sociology

Questions about urbanization and community change have been central to sociology since the founding of the discipline. 200 years later, the world continues to urbanize at a remarkable rate, and the study of urban social worlds remains a central task for social scientists. At present, more than half the world’s population lives in an urban area, and by 2050, it is expected that 68% of the global population will reside in such areas. In the United States, an estimated that 83% of the population currently lives in an urban area, and by 2050, that percentage is expected to climb to 89%. In this course, we will take a sociological approach to questions of community, built environment, and urban life. In particular, this course asks you to explore urban social worlds as places of possibility and inequality. In so doing, we will consider what makes urban “community,” think about the relationship between “urban,” “suburban,” and “rural,” and unpack social problems and solutions commonly associated with urbanization and urbanism.

Environmental Sociology

When we hear the word “environment” we often conjure up mental images of untouched and tree covered mountain ridges, secluded waterfall oases, and pristine babbling brooks. But the environment – or nature, for that matter – is not the absence of human presence. While idyllic, such images often ignore the fact that environment is necessarily defined by and through social interaction, culture, and social institutions.

Over the course of this 16 week course, we will consider the intimate and often problematic relationship between society and environment. Through this relationship, we both shape the environment and are shaped by it. We’ll pay particularly close attention to common environmental problems of our own creation – including but not limited to the climate crisis, water and air quality, and capitalist consumption and accumulation. We’ll also dedicate ample time and energy to understanding how inequalities are (re)produced through use of and engagement with the environment/ecological systems and how our sociological imaginations can be useful in our search for a more sustainable future.

Introduction to Sociology

Chances are, you are familiar with the word “sociology,” but few of us are likely to really understand what sociology is. Yes, of course, sociology is the study of society. It’s the study of people and how they interact. It’s the study of groups. All of this is true. BUT this is all very vague and roughly describes other popular social science disciplines like psychology and anthropology. This course treats sociology as a unique perspective, and by the end of the semester, students in this course will be well practiced at viewing and interpreting the world through this lens.

As a warning, know that the sociological perspective is often at odds with common sense, and learning to view the world in this way does not come easily to everyone. However, learning to view the world in this way has its benefits. Principally, learning to see racism, sexism, poverty, health disparities, etc. as a product of structural patterns can provide us with insight into solving and abating problems of (social) inequality.

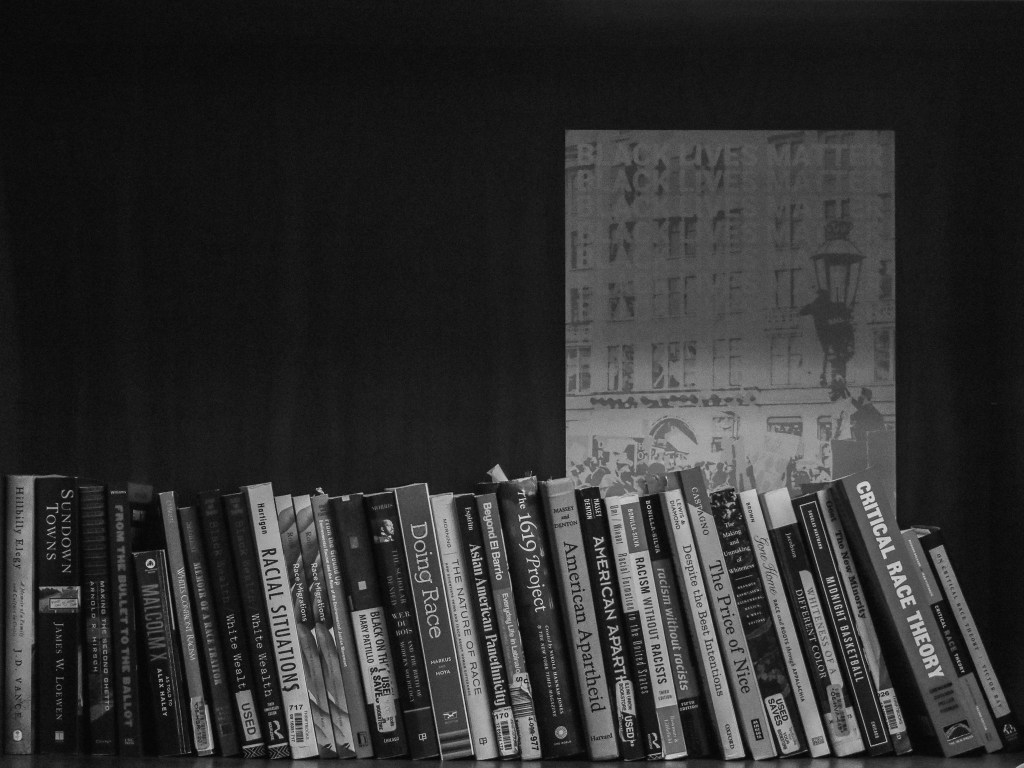

Race and Racism

What is race? Undoubtedly, students are familiar with the word, but answering this question can be difficult. Race is the product of a many generations of historical processes. It is a social construction, but it also has material consequences. It is hard to define, yet we all know (or think we know) what it is. As a concept, it overlaps and intertwines with other constructs like nationality, gender, class, and religion. What it means to white, black, Latinx, Asian, Native American, etc. will vary by context. We each identify with particular racial categories, yet race is also an externally assigned status. How we understand race is intimately tied to the way we see the world and how we interact with those around us.

To say the least, studying race (and ethnicity and racism) is a complicated endeavor. The effects of race are also complicated, diverse and often overlooked. Issues of race and racism continue to plague the contemporary US and other societies. On each of us, race and racism differentially impose social, emotional, psychological, material, and enduring consequences. Thus it is important that we consider and critically reflect upon interpersonal interaction, institutional arrangements (e.g., institutional policies), and cultural understandings that might produce racial inequalities.

This course starts with the position that race and ethnicity are social constructs and challenges students to use a constructionist perspective to analyze race relations and social inequality in multiple contexts. In this course, students will NOT be able to explore all topics important to race and racism — far from it. Instead, the primary goal of this course is to provide students with a foundation for understanding race and racism through a sociological lens. Such a foundation will enable students to move on to more advanced examination of the topic, and more importantly, think about the ways race and racism are relevant to the social world(s) they help create.

Social Stratification

Our world is rife with social inequalities. That said, it’s important that we seek better understanding of how, where, and in what form these inequalities are produced and maintained. In this course, we spend 16 weeks considering the importance of three overlapping systems that produce and maintain social stratification: capitalism, white supremacy, and patriarchy. Through these systems, we examine disparities in wealth, income, health outcomes, political power, and social and cultural capital. Approaching these topics from a sociological perspective not only gives us a stronger understanding of the way our world operates but should also spur ideas for how we can disrupt systems that promote the uneven distribution of social, political, cultural, and economic resources.

Social Research Methods

Students who have already taken sociology courses with me have undoubtedly heard me say some version of: “Sociology is a perspective. It’s an alternative way of seeing the world that is often at odds with ‘common sense.’” Great – so how exactly do sociologists (and other social scientists) come to this alternative view? How does this process differ from casual observations? In large part, it’s about the ways in which we gather, interpret, and analyze information (data).

This course provides an overview of research methodologies used in the social sciences. We’ll consider a wide range of methodologies, including survey research, ethnography, interviews, and historical comparison. We’ll also consider the steps involved in a research study, including reviewing of the literature, developing a question, collecting data, and conducting analysis (and the many smaller steps in between).

While these are the tools used by academic social scientists, it’s worth noting that the skill set you develop in this course has utility well beyond the walls of the classroom. Going through this process teaches us to be critical and provides us with a baseline understanding of what constitutes “good data” or “good science” in an age where misinformation spreads rapidly. Further, employers, ranging from nonprofits to human resource departments to tech giants increasingly value those who can conduct social research. Likewise, those in public policy, community development, and grassroots organizing often look to social scientists for guidance. So, not only will this course help you better engage with the world around you, students who excel in this course are setting themselves up for successful careers and impactful community opportunities.